By : Lloyd Mahachi

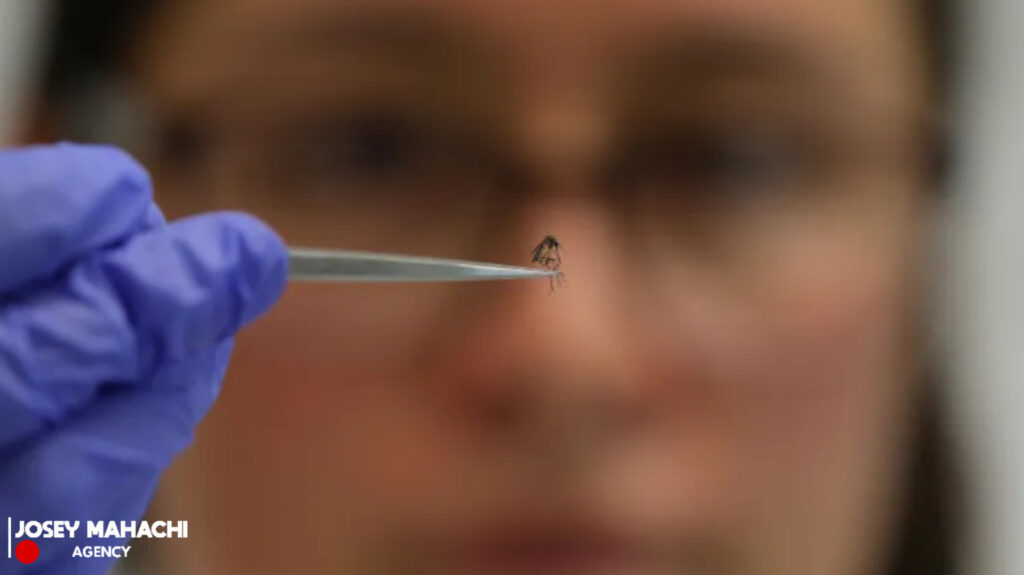

Mosquitoes are typically associated with serious diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, and yellow fever. However, researchers from Leiden University Medical Center and Radboud University in the Netherlands have found a new role for these insects: as vaccine distributors. They have successfully engineered mosquitoes to deliver vaccines that could potentially provide enhanced immunity against malaria.

The World Health Organization’s most recent World Malaria Report revealed that an estimated 597,000 people died of malaria globally in 2023, with African countries bearing the brunt of the death toll. Scientists estimate that over 240 million malaria cases occur annually worldwide, with children and expectant mothers being the most vulnerable to the disease.

The vaccine employs a weakened strain of Plasmodium falciparum, the parasite that causes the deadliest form of malaria in humans. According to vaccinologist Meta Roestenberg, the parasite has been genetically modified to remove an important gene, allowing it to infect people but not make them sick.

The vaccine is delivered via mosquito bites, mirroring the natural transmission of malaria. The goal is to create a strong immune response in the liver and provide protection from malaria infection. The research team used mosquitoes carrying the modified parasite to deliver the vaccine, intending to create a strong immune response in the liver and protection from malaria infection.

The first trial tested an injectable malaria vaccine derived from a genetically modified parasite. The study involved 67 participants from two cities in the Netherlands and showed that the vaccine was safe to use and delayed the onset of malaria but did not prevent participants from getting the disease.

In the second trial, participants received mosquito-delivered versions of two vaccines. The results showed that 13 percent of the participants who received one vaccine developed immunity from malaria, while 89 percent of those who received the other vaccine developed immunity. No one in the placebo group developed immunity.

Further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of the vaccine in larger studies and to determine how well it boosts the immune system over longer periods. Additionally, more research is needed to determine whether the vaccine can protect against different strains of the malaria parasite in areas where the disease is common.

Using mosquitoes as a vector for delivering vaccines is a new approach, but it is not without its challenges. While it may be easier and quicker to deliver malaria sporozoites via mosquito bites, it is not a sustainable solution for large-scale vaccine delivery. The vaccine will need to be developed as a vialled vaccine to be rolled out in Africa.

Mosquitoes have been used to deliver vaccines before, but this is a relatively new area of research. In 2010, Japanese scientists genetically modified mosquitoes to carry a vaccine against leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease typically spread by sandflies. In 2022, a study in the United States explored the potential of mosquitoes as vaccinators, using genetically weakened malaria-causing Plasmodium parasites.

The use of mosquitoes as vaccine distributors is a promising area of research, but it is still in its early stages. Further studies are needed to determine the effectiveness and safety of this approach, but the potential benefits are significant. If successful, this approach could provide a new tool in the fight against malaria and other diseases spread by mosquitoes.

The development of a mosquito-delivered vaccine has the potential to revolutionize the way we approach malaria prevention. Traditional vaccine delivery methods can be time-consuming and expensive, but using mosquitoes as a vector could provide a quicker and more cost-effective solution. Additionally, this approach could be used to deliver vaccines against other diseases spread by mosquitoes, such as dengue fever and yellow fever.

Overall, the use of mosquitoes as vaccine distributors is a promising area of research that could have significant benefits for global health. While there are still many challenges to overcome, the potential rewards are significant, and further research is needed to explore this approach.

Editor: Josephine Mahachi